You can cut and paste this letter into “they work for you” and email it to your MP. If you...

Meeting of President Gustavo Petro and President Donald Trump – What was the outcome?

On 3 February 2026, there was a meeting between President Gustavo Petro and President Donald Trump in the White House....

How is Macro Case O1 on Kidnapping related to obtaining truth and restorative justice for victims of conflict related sexual and gender-based violence?

The Colombian Commission of Jurist explains the importance of the final analysis by the judges on this case for Macro...

Important Electoral Moment in Colombia’s History

In 12 days on Sunday 8 March 2026, Colombia will hold Congressional Elections. There are considerable concerns for the safety...

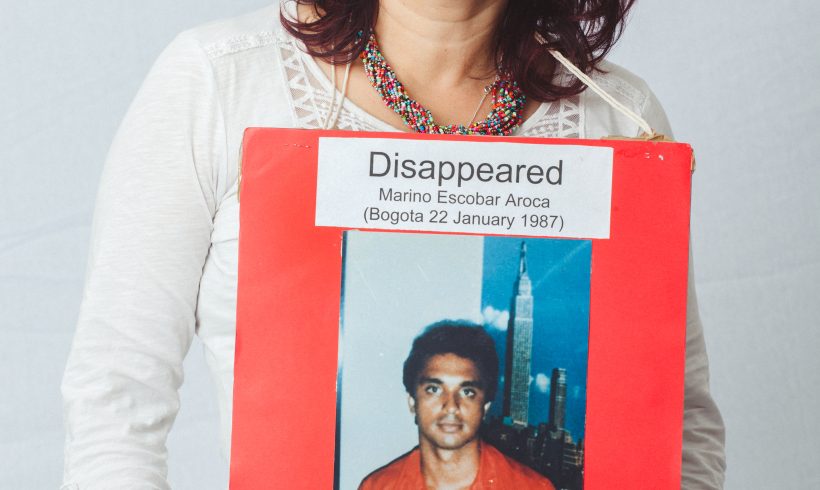

Remembering Marino Escobar Aroca, and Recognising the Tireless Work of Women Searchers

On 17 October 2025, following a long and painful struggle by the family of Marino Escobar Aroca, the President of...

ISDS a threat to global security

On 4 February 2026, parliamentarians, civil servants, experts, campaigners, academics, and community representatives gathered in the UK Parliament for a...

Attempt on the life of Environmental Human Rights Defender Misael Socarrás Ipuana – letter to the National Protection Unity (Spanish)

18 de diciembre de 2025 Asunto: la grave situación de seguridad del defensor de los derechos humanos y ambientales Misael...

Attempt on the life of Environmental Human Rights Defender Misael Socarrás Ipuana – Letter to the Prosecutor General (Spanish)

18 de diciembre de 2025 Asunto: la situación de seguridad de Misael Socarrás Ipuana Estimada fiscal general de la Nación,...

Attempt on the life of Environmental Human Rights Defender Misael Socarrás Ipuana – Letter to the Minister of the Environment

18 de diciembre de 2025 Estimada ministra, Me dirijo a usted en nombre de ABColombia, una organización formada por cinco...

Attempt on the life of Environmental Human Rights Defender Misael Socarrás Ipuana – Letter to the Minister of the Interior (Spanish)

18 de diciembre de 2025 Asunto: la grave situación de seguridad de a Misael Socarrás Ipuana y los defensores y...

Joint Statement: Alarm Bells Ring as UK Support for Human Rights Defenders Takes a Back Step

At a time when the targeting of those bravely defending human rights and the environment has reached crisis point, the...