You can download the report in English and Spanish.

The context

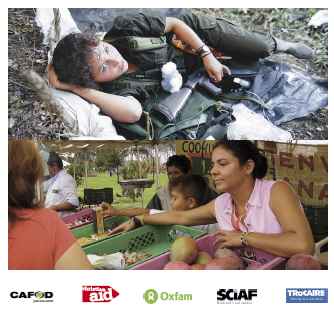

More than 70,000 people have been killed in Colombia in the past 20 years as a result of an extremely violent conflict in which all sides target the civilian population. The military campaign carried out by the Colombian army since 2002 has achieved an important shift in the strategic balance of the conflict with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

However, despite some welcome gains, many aspects of Colombia’s economic, social and political life are deteriorating. Small improvements in poverty levels as a result of recent economic growth are unlikely to be sustainable in a downturn, as structural causes have not been addressed. Poverty levels in rural areas are still as high as 62%. Meanwhile, inequality has worsened considerably. Land distribution, a root cause of the conflict, is more unequal than ever, with 0.4 per cent of landowners now owning 61% of rural land. Colombia is suffering one of the worst humanitarian and human rights crises in the world, finding its clearest expression in the continuation of the world’s second worst internal displacement crisis (after Sudan). Colombians are forced to flee by armed groups seeking to establish territorial and economic control, or are simply caught up in the violence. Between 3 and 4 million people have fled their homes in the past two decades, and Colombians make up the third largest refugee population in the world. In 2008 there was a sharp increase in forced displacement.

Civil society organisations, trade unionists and journalists seeking to expose crimes and human rights violations, or calling for different development policies, do so at the risk of violence and death, as Colombia continues to be one of the most dangerous places in the world in which to carry out these activities. Despite the paramilitary demobilisation, a new generation of paramilitary groups is consolidating power at local and national levels. Selective assassination, disappearances, massacres and threats against human rights defenders, trade unionists, social leaders and political activists are commonplace. Though there have been some advances in high-profile cases following international pressure, impunity for these crimes remains the norm in Colombia.

British Government policy

The British government has stated two objectives in Colombia: to support efforts to reduce human rights abuses in Colombia, and to reduce the flow of cocaine coming into the UK. Unfortunately, progress on the second of these areas has been as disappointing as on the first. Despite some high-profile seizures and arrests, cocaine prices are falling in the UK, implying that supply is as plentiful as ever.4 Colombian government policies, such as fumigation and manual eradication of the coca plants, have failed to stem cocaine production, which stands at an estimated 600 tonnes per year, about 60 per cent of world cocaine production in 2007.

In particular, both the British and Colombian governments need to respond to the root causes of the conflict: inequality, political exclusion and the repression of dissent. Cocaine production, human rights abuses and the continuing armed conflict will not be ended by military responses or protective measures alone. Rather, a significant shift in economic and social policies is required to reduce poverty and inequality, including the participation of the most vulnerable sectors of the Colombian population. Only then will the cycle of violence that has blighted the lives of so many Colombians, especially the poorest and most marginalised, be interrupted.

In this context, the British government must pay special attention to the role British business plays in Colombia, and ensure that it is supporting human rights and poverty reduction, not undermining these objectives. Equally, the UK needs to open its books on the controversial assistance programme to the Colombian military. In recent months there has been a change of government in the United States and, thanks to strong civil society advocacy in Colombia and the US, the US government has announced a shift towards more development assistance and less military assistance in the context of Plan Colombia. There is a new British ambassador in Bogotá and a new UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office minister with responsibility for Latin America. In Colombia the 2010 presidential election is already looming large on the political landscape. These changes open a window of opportunity for important shifts in policy towards Colombia and make the moment opportune for ABColombia to publish its contribution to that endeavour. We urge the British government to use all the tools at its disposal to defend human rights and promote sustainable, pro-poor development in Colombia.