The Delegation consisted of two meembers of the Dáil (Irish Parliament): Fiona O’Loughlin TD, and Senator Catherine Noone, and one member of the UK Parliament: Baroness Jean Coussins. They were accompanied to Choco by a representative of the UK Embassy in Colombia, Tom Newton and the Scottish National Agency for International Development (SCIAF), Christian Aid and ABColombia.

Visit to Choco: to Quibdo (capital of Choco) and Afro-Colombian

Collectively owned Territories of Villa Conto, San Isidro and Paimadó.

In Choco the delegation visited the Afro-Colombian communities of the Collective Territories of Villa Conto, San Isidro and Paimadó. In order to visit these communities the delegation had to travel up the river Quito (Rio Quito) a tributary of the Atrato River.

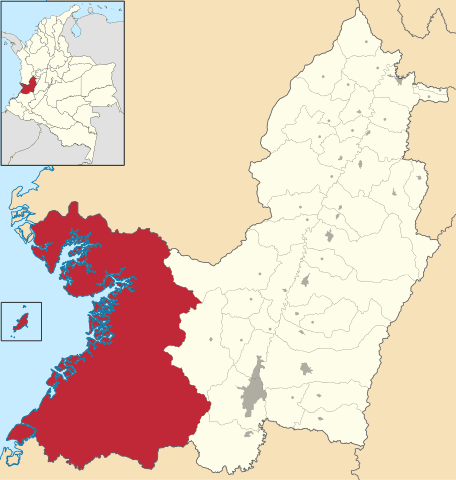

Chocó runs along the Pacific coast of Colombia, situated between the Darién Gap on the border with Panama and the departments of Antioquia and Valle de Cauca. It is one of the planet’s most biodiverse regions, with about 2,000 species of endemic fauna and flora. It has rainforest, large fast flowing rivers and some of the largest mangroves in the region. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) considers it is one of 17 priority sites for conservation in the world.

Unlike any other Colombian Department, 95 per cent of the population is Indigenous and Afro-descendant, living on collectively owned land. Their livelihoods revolve around hunting, fishing, farming and small-scale artisanal mining. Until the 1990s this way of life preserved the rich biodiversity and, in turn, met the communities’ basic needs. However, in 1997, there was a joint military-paramilitary offensive known as Operation Genesis, which caused terror amongst the population and drove mass forced displacement. The State Observatory, at that time, registered an intensity in the conflict that had ‘rarely [been] seen’ in Colombia.

Chocó is a department rich in gold and platinum. For centuries, artisanal mining (without the use of toxic chemicals) benefited the Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities. In the 1980s gold rush, miners arrived in Chocó with mechanical diggers and dredgers. They started using mercury to separate out gold and washing the residue into the rivers. In 2009, a government commission revealed that four tons of mercury had been washed into Río Quito, Chocó. By 2010, Colombia was the world´s worst mercury polluter per capita from small-scale mechanised gold mining, and Chocó one of the worst areas in Colombia. Uncontrolled small-scale mechanised mining in Chocó has also proved to be a lucrative business for illegal armed groups and contributed to fuelling the conflict.

Communities Reported a lack of protection by State Security Forces

Fuerza de Tarea Conjunta Titán have been deployed in Choco which is a joint force comprising of the Army, Navy and Air Force. It has been deployed in Choco since 2014.

- In Chocó, Buenaventura and along the rivers of Bajo Calima, Bajo San Juan and Rio Quito, reported that rather than seeing a decrease in violence they had experienced an increase in the situation of insecurity since the signing of the Peace Accord.

- Quibdó: the delegation met with Coronel Franco of the Joint Forces Titan and the CR John Milton Arevalo Rodriguez of the Police Force.

- The delegation visited communities in the Rio Quito and noted that there was a military check point at the entrance to the Rio Quito a tributary of the Atrato River. Despite the military check point controlling the entrance to the Rio Quito illegal armed groups transited the rivers with apparent ease leading to the delegation concluding that there must exist a level of collusion between the security forces and the illegal armed neo-paramilitary groups.

- With the departure of the FARC-EP from Chocó, the dynamics of conflict have changed between the illegal armed groups, paramilitary successors / dissidents and the National Liberation Army (ELN), which are in dispute for territorial control. At the same time, there have been combats between the State Security Forces and the aforementioned groups.

Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) and the ELN in the Rio Quito, Choco

- In Rio Quito, the neo-paramilitary groups, mainly the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) and the ELN, were either operating extortion rackets or directly controlling the mining that is operating illegally in the river.

- They were also reported to be threatening and intimidating the communities and particularly the leaders representing the communities that had been elected to the various consejos comunitarios. Whilst the delegation was in Chocó, one of the leaders received several menacing calls.

- Despite several early warning alerts (SATs), there have been extremely high levels of mass displacements in Choco due to combats and threats with some 2,500-people displaced and about 320 confined in 2016.

Rio Atrato and Rio Quito Gold Mining and illicit crops

- The illegal use of the mechanised equipment for gold mining in the Rio Quito was very evident along the whole of the river. The first machines -diggers and dredgers -for extracting the gold from the river bed were seen on the river Atrato next to bank on the opposite side of the river to the Police Station. The Police station looked directly at this. The next ones were only 10 minutes away from Quibdó at the beginning of the Rio Quito.

- As we progressed along the river Quito we noted that some of the small mining platforms floating in the river had been burnt. This had been done by the security forces in order to remove these illegal operations from the river. However, it was reported to us that the costly equipment for excavating the gold had been removed the night before the security forces came to burn the platform. This could only have happened if there had been someone from inside these Forces passing information to the illegal mining owners/workers. It was then relatively easy, and not too costly, to re-initiate these operations.

- In addition to gold mining three are groups operating in the Rio Atrato and its tributaries that control the cultivation and trafficking of coca (illicit crops), these operations also generate similar violence to that of illegal gold mining.

Sentence T-622

- The communities in the Rio Quito area, one of the tributaries of the Atrato River, have a very high level of organisational capacity; along with good legal advice from organisations like Tierra Digna; and well-developed initiatives with local, national and international experts for addressing the contamination in the Rio Quito; all of which was very impressive.

- As a result of the work of Tierra Digna with the Communities they won a landmark legal decision in which the Colombian Constiutional Court adopted an unprecedented ecocentric approach to human rights: and recognised the Atrato River and its tributaries (including Rio Quito) as a legal entity with environmental rights that need to be protected alongside the communities’ bio-cultural rights. Thus, the Court acknowledged the inherent interdependency between the environment and communities in the Atrato region.

- The Court ordered the Government to take a series of measures to protect the Atrato River and combat illegal mining in the region while taking account of “the environmental and social realities of the nation”. The Court also reiterated once again the right to free, prior and informed consent for ethnic communities.

- The delegation learnt that the sentence T-622 included specific criteria for consultation with the communities and outlined how they should have a central role in elaborating plans for the implementation of the decidsion which not only included de-contamination of the river but also state support for the communities to develop their collectively owned territories. It was therefore concerning to learn from the communities, that so far they had not been consulted on the implementation measures, despite plans already being drawn up by various entities in relation to this ruling.

- The delegation was well aware of the importantce of community participation, to ensure that projects address the needs of the community and are sustainable in the long term.

Peace Process with FARC in Choco

Choco: 31 January 2017, the process of transferring the members of the FARC to the two Temporary Transition Points (PTN) designated for the department was completed, leaving power vacuums in the areas they were occupying. As a result, there were violent disputes across Choco which were at their height in March 2017. These were between the illegal armed groups, namely, ELN and neo-paramilitary groups for control over people, land and the lucrative illicit economies. These armed disputes resulted in forced displacement of communities during the first six months of 2017 there were sixteen massive forced displacement resulting in 4,525 victims, 37.46% were indigenous and 66.08% were Afro-descendants. When compared to the national total of people forcibly displaced, Choco represented 57.4% of the total. (According to the presentation given to the delegation by UMAIC).

Humanitarian Crisis in Choco

UMAIC also explained to the delegation that in 2016 nearly 60% of the population in Choco lived in poverty; and only 64.9% of the children in Choco are covered by education services.

The Diocesis of Quibdo explained that when comparing quality of life statistics between Choco and other regions of Colombia, the differences are considerable: as of 2014 in Choco approximately 81 percent of people have their basic needs like potable water unmet, compared to the national average of 37 percent. Quibdó was a city of internal refugees, as more than half (52 percent) of the city’s residents in 2012 had arrived due to forced displacement.

Child forced recruitment in Choco was carried out by the neo-paramilitaries (Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia) and the Guerrilla Group (Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional – ELN) as well as, incursions, combats, confrontations, threats, kidnappings, selective homicides and injuries from anti-personnel mines. The laying of anti-personnel mines has particularly affected the communities, in one case the ELN laid mines close to a school.

There is a humanitarian crisis in Chocó. Mining (both illegal and legal) is a key factor in fuelling continued conflict in Chocó, and a major obstacle to implementing a lasting peace in the region.

Some areas in Chocó continue to experience high-levels of violence and forced displacement of communities. Neo-paramilitary groups (referred to by the Colombian Government as “Criminal Gangs” -BACRIM) and the second largest guerrilla group in Colombia, the ELN, have been fighting for control of the drugs trade and illegal gold mining.

As a result of this difficult context the citizens of Choco organised a huge social protest regarding the humanitarian situation and demaded that the Colombian government provide basic serivces that would enable them to have a a dignified life: improvements to roads, health care, education, basic infrastructure, unemployment, public services, and electricity, among other demands.

The Bishop of Quibdó gave the delegation a copy of the demands made by the citizens entitled “Humanitarian Accord” (Acuerdo Humanitario Ya!). This document includes a series of recommendations, many of which relate to the lack of crucial basic services.

The communities have their own development plans, and alternative visions of development that often comes from their cultural heritage.

The full implementation of this Accord, and previous commitments made by the Government to Chocó, in terms of local services and infrastructure, is something the delegation promised Bishop Barreto to monitor over the coming months.

Chocó urgently needs support to develop new technologies to ecologically restore areas affected by illegal gold mining. UK academic and political institutions can play a leading role in this, together with their Colombian counterparts.

Wounaan Communities in Bajo San Juan and Bajo Calima Rivers

Delegation of parliamentarians met with the Wounaan Nonam Indigenous Peoples along the San Juan river in the South West of Colombia, living on the Reserves (Resguardos) of Santa Rosa de Guayacán in the river Calima and Union Agua Clara, in the Bajo San Juan River. They were accompanied by ABColombia, Christian Aid, the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace (Comision Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz- CIJP), and CONPAZ.

- When visiting the Santa Rosa de Guayacán and the Agua Clara villages of the Wounaan Indigenous Peoples along the Bajo San Juan and Bajo Calima rivers, it became quickly evident that they faced a situation of insecurity and vulnerability despite the State Security Forces being present at all the entrances and exits to the Bajo San Juan river.

- These communities had suffered forced displacement, been trapped in their territory, seen massacres and continue to feel abandoned and unprotected by the State.

- The transiting of the river by the neo-paramilitary group the AGC and the ELN has made combats for control of the rivers more prevalent, communities have been threatened, curfews imposed, and confinement in their territory has meant that they are unable to carry out their normal daily activities of hunting, gathering and cultivating, which has resulted in a situation of food insecurity.

- High velocity boats, the type used by drug-traffickers and neo-paramilitary groups, transit this river at night, despite there being a curfew in operation and navy checkpoints.

- There have been kidnappings and killings, which have generated a well-founded fear in the communities.

- The Wounaan Nonam Indigenous villages of Santa Rosa de Guayacán, River Calima and Unión Agua Clara have been forced to displace due to neo-paramilitary incursions and threats by other armed groups.

- Despite Governemnt policies in place that provide for dignified returns, one of the major issues for these communities has been that the municipal authorities have either not provided an adequately resourced plan and/or not fully implemented the few commitments made. This has left the Wounaan in a precarious situation.

- By way of an example, only about 5% of the return plan agreed between Santa Rosa and the Municipal Authorities of Buenaventura has been implemented.

- As a result of both forced displacement and confinement in their territories communities have been unable to cultivate, harvest, fish, and hunt, which is the subsistence economy of these communities, which has left communities with insufficient food.

- The community showed the delegation food that had arrived two days before, as part of the commitments in the return plan; it was in a deplorable state: food pulverized or dried-up due to packets being open and much was unusable. In this community, it was noticeable that people were hungry and that there was insufficient food to eat

Union Agua Clara

The community of Agua Clara, were forced to displace in 2010. Due to a lack of State provision they were forced to live in a small local sports stadium in the city of Buenaventura, in some of the most appalling conditions, which included no electricity or water. Having given up hope of the State ensuring a dignified and safe return, the Agua Clara community returned alone.

The Wounaan in Santa Rosa de Guayacán displaced again on 11 February 2017, following a paramilitary incursion into their village, they had not long returned when the parliamentarians visited.

“The people of Agua Clara have suffered a major trauma, in having to leave their homes and live in such terrible conditions for over a year”. Senator Catherine Noone

The delegation visited Santa Rosa de Guayacán and the Agua Clara villages of the Wounaan Indigenous Peoples in the Bajo San Juan and Calima rivers in the Litoral de San Juan municipality and in rural areas of the Buenaventura. Where it became quickly evident that they faced a situation of insecurity and vulnerability despite the State Security Forces being present at all the entrances and exits to the river.

The communities reported that the transiting of the river by the neo-paramilitary group the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) and the ELN has made combats more prevalent. There river itself is a major drug trafficking route and high-speed boats are heard passing along this river at night. Communities reported to the delegation that their movements were severely restricted due to threats and fear. These two illegal armed groups were competing for control in the area.

The abuses the communities reported included:

- Armed groups limited their ability move freely in the river they were experiencing curfews and confinement in their territory which meant they were unable to carry out their normal daily activities of hunting, gathering and cultivating, this has resulted in a situation of food insecurity.

- High velocity boats, the type used by drug-traffickers and neo-paramilitary groups, transit this river at night, despite there being a curfew in operation and Navy checkpoints. In addition, there have been kidnappings and killings which have generated a well-founded fear in the communities.

The community showed the delegation food that had arrived two days before, as part of the commitments in the return plan; it was in a deplorable state: food pulverized or dried-up due to packets being open and much unusable. In this community, it was noticeable that people were hungry and that there was insufficient to eat.

Fiona O’Loughlin stated: “the Wounaan told us of their fear of the armed groups that transited the river, these armed groups forced them to displace in the past, now they remain trapped in their territory unable to hunt and fish, and with no meaningful access to healthcare. They told us that children have died from simple things such as diarrhoea. Peace will only be possible and sustainable in Colombia if communities like the Wounaan are safe in their territory and have access to basic services.”

The Wounaan Nonam Indigenous villages of Santa Rosa de Guayacán, River Calima and Union Agua Clara have been forced to displace due to neo-paramilitary incursions and threats by other armed groups. One of the major issues for these communities has been, despite Governemnt policies in place that provide for dignified returns, the municipal authorities have either not provided an adequately resourced plan and/or not fully implemented the few commitments made. This has left the Wounaan in a precarious situation. By way of an example the April 2017, the community report that only about 5% of the return plan agreed between Santa Rosa and the Municipal Authorities of Buenaventura has been implemented.

Buenaventura in Valle de Cauca Department

Buenaventura, a town of 400,000 inhabitants, expanded its port with a major injection of foreign investment (FDI) to become the busiest in Colombia. It manages approximately 60 per cent of Colombia’s internationally traded goods. At the same time more than 80 per cent of the population lives in poverty, and supplies of electricity and water are unreliable, it is one of the country’s least developed cities. Despite being a highly militarised town the PDPGs groups have a strong presence. According to official figures (Attorney General’s Office and the Interior Ministry 2015), in the last 20 years Buenaventura has seen, 26 massacres, 160,000 persons forcibly displaced and more than 6,000 people killed, in a struggle for territorial, economic, and social control. In this context and at a time when the violence was increasing with the introduction by the neo-paramilitary groups of ‘Chop Houses’ (casas de pique) where people were taken forcibly by the neo-paramilitary groups and dismembered alive. According to the locals their screams were heard by all the community and such practices were used to terrorise the community.

On the other hand, security guarantees exist for the business sector of the city, in the form of the large port used for international trade. Trade into this Port has been boosted and consolidated through the various Free-trade Agreements and, specifically trading with the Pacific Alliance countries. A variety of projects have been carried out such as, the port expansion and the construction of a dual carriageway to respond to the increase in global market trade. This expansion displaced the afro-Colombian population of Bajo Calima from their territorial land.

“What seems strange to us is that this type of economic activity is not affected neo-paramilitary violence in Buenaventura. It appears that the violence has been directed exclusively at the afro-Colombian populations who are legitimate owners of territories in the pacific zone.”

The delegation were told that in the Urban area of Buenaventura, control is exerted, not through the State but by neo-paramilitary structures in 90% of the neighbourhoods. This control is exerted over all of the commercial enterprises which have to pay extortion money e.g. informal street vendors, petrol stations and taxi drivers and boats owners etc.

The population of a few streets which contained traditional fishing houses built on stilts in the river due to the violence that they were expereincing asked the Inter-Church Commission for Justice and Peace (Comisión Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz -CIJP) to set up a “Humanitarian Space”. The Puente Nayero Humanitarian Space, is located in the neighbourhood of La Playita in the town of Buenaventura, is a series of waterfront streets where houses are on stilts in the sea with raised walk ways. The Afrodescendent community live off artisanal fishing and logging. When the delegation visited a newer Space was being developed called Puente Icaco Humanitarian Space.

This Humanitarian Space offers protection from extortion and widespread violence, it no longer has a ‘chop house’ and other families have moved there for their protection. Whilst, in general, safety has increased dramatically for the people living in the Humanitarian Space there are still threats. Despite this Humanitarian Space is demonstrating in a town, where populations were controlled and terrorised by illegal armed groups, that change is possible.

Findings of the delegation in Buenaventura

- The importance of the Buenaventura Port for international trade was something that caught the attention of the delegation, especially since the port expansion threatens to displace communities like that of Puente Nayero and Punta Icaco.

- These two communities are self-declared Humanitarian Spaces and due to their special status have succeeded in improving the security situation for those living there.

- The ideas that the community has for the development and inclusion in the tourist plan for Buenaventura are commendable and need to be supported by local and national authorities.

- Inclusive development is an essential element for peace building and for communities to experience the peace dividend.

- Engagement of central and municipal government with the Puente Nayero and Punta Icaco Humanitarian Spaces is essential to ensure that they fully participate in planning meetings and that their development ideas for their community are incorporated into the municipal development plan.

- National and international accompaniment, special protection measures from the IACHR, has increased security for the community and their leaders.

- Documenting and denouncing abuses by CIJP as well as their engagement with networks of publicity and generating visits from the diplomatic community raised the profile and subsequently the safety of the Humanitarina Spaces

- The Humanitarian Space provides a beacon of hope that change is possible.

Civic Strike in Buenaventura.

In May 2017 a few months before the delegation arrived in Buenaventura, an alliance of community and grassroots organisations in Buenaventura organised an indefinite civic strike to protest against the State’s historic neglect of the Afro-descendant population.

The protesters eight core demands were related to the provision of basic services to allow communities to live with dignity: quality healthcare and a hospital, access to education, drinking water and dignified employment opportunities. They also protested against the environmental destruction in the area and asked for justice for victims of violence.

Those who had taken part in the Civic Strike explained to the parliamentarians that they had been subjected to human rights violations at the hands of the anti-riot police (ESMAD) as they tried to supress the civic strike. They also reported that they continue to be stigmatised and threatened by neo-paramilitary groups.

The Civic Strike was eventually lifted after agreements were signed with the Colombian government. However, they reported that little has changed since then. The agreements had not begun to be implemented and the leaders of the civic strike

Human Rights Defenders, social protest and impunity

- The number of human rights defenders killed in recent years (458 between 2009 and 2016) is of grave concern. According to Somos Defensores 57% of the 51 defenders killed so far in 2017 were killed by neo-paramilitarygroups. We heard very similar reports whether leaders were defending environmental, labour or community rights. All defenders were experiencing stigmatisation, threats and attacks, the majority identified the perpetrators as neo-paramilitaries, others identified the ELN, and in many cases the perpetrator was unidentified.

- The reported use of excessive violence by ESMAD during the policing of protest marches was concerning both in Buenaventura and Quibdó.

- Concerns were specifically expressed about the high levels of impunity: according to one lawyer, who cited a report from the Attorney General’s Office, there were only five sentences in 2016 for crimes against defenders and there were 80 defenders assassinated. The continued impunity for these crimes is a major issue in terms of dissuasion.

The Delegation’s impressions of progress in relation to peace

- The Delegation were very impressed with the achievement of the Peace Accord with the FARC. This deal is far more comprehensive and integrated than other countries have managed to date.

- The global precedent set by the Colombian Constitutional Court in its landmark ruling T-622 of 2016, was also an impressive global first and has much to contribute beyond Colombia’s borders.

- The recent announcement of a temporary bi-lateral ceasefire with the ELN is also very encouraging and we hope a Peace Accord with them can be obtained before this ends in January 2018.

- Many of the security issues we saw were due to the actions of the neo-paramilitary groups; we were therefore please to see that on 3 September 2017, the ‘Clan del Golfo’ stated that they wished to submit themselves to the Justice System. It will also be important to successfully dismantle all the neo-paramilitary groups and their backers.

Puente Nayero

After their visit the delegation

Sent a letter to the Colombian Presidential Advisor for Human Rights, Paula Gaviria, highlighting the precarious living conditions of communities in Buenaventura. Read the full correspondence here.

Read the response by Paula Gaviria, Colombian Presidential Advisor for Human Rights https://www.abcolombia.org.uk/letter-paula-gaviria-2017/

Watch the videos of the parliamentary delegation to hear further statements by the parliamentarians.