Mary Lawlor UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) December 2020 report states that of the 1,323 killings of defenders 933 of those were killed in Latin America and the Caribbean. This is the region of the world which has consistently been the highest in terms of killing of HRDs and Colombia has consistently remained the most deadly country in the world.

Only counting the number of killings of HRDs however fails to show the extreme conditions that HRDs in Colombia have to contend with in order to defend the rights of others and the rights of nature. In May of 2020, Semana reported that military intelligence had been gathering information on HRDs, journalists, the political opposition and others; this was called ‘Operacion Baston’. It was revealed that there was a recurring practice of selling information and weapons, as well as, alliances with some illegal armed groups to weaken others. These events implicated 16 generals and around 230 officers and sub-officers. Also in May 2020, the authorities found secret official documents in the possession of drug traffickers. This combined with information published on the Security Doctrine by the New York Times, (Colombia Army’s New Kill Orders Send Chills Down Ranks, Nicholas Casey, 18 May 2019) suggests that there continues to be a National Security Doctrine that focuses on the “the enemy within,” has furthered calls for the removal of the Police from the Ministry of Defence and its creation under the Ministry of the Interior as a civilian Police Service, to open the way for a Doctrine of Security for Peace.

According to Somos Defensores, of the aggressions and killings against HRDs in 2019 and the first six months of 2020, where the perpetrator was identified, the group most responsible were the neo-paramilitary groups. It is also possible that the pandemic has created a more complex situation and that neo-paramilitary activities were ‘outsourced’ through other criminal structures or gangs, which has made it difficult to identify who is responsible.

Violence in Rural Areas

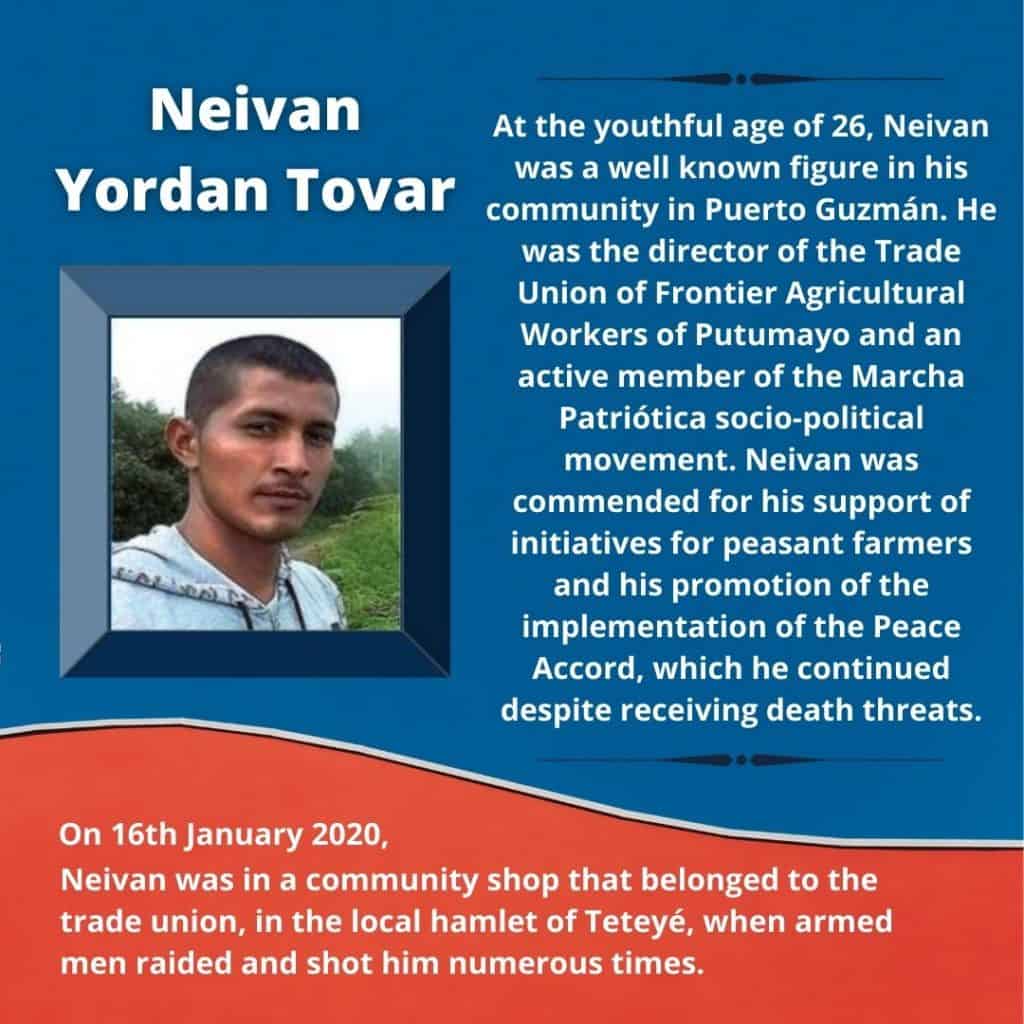

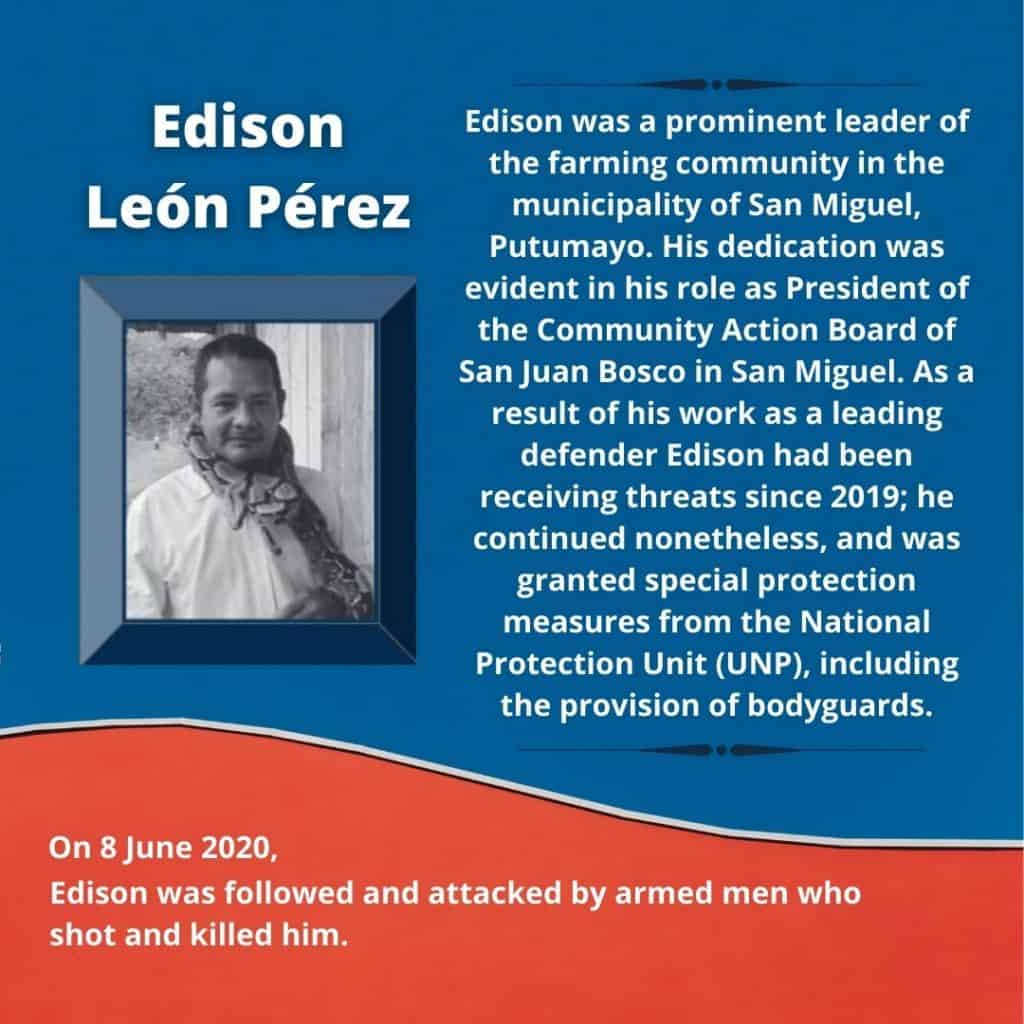

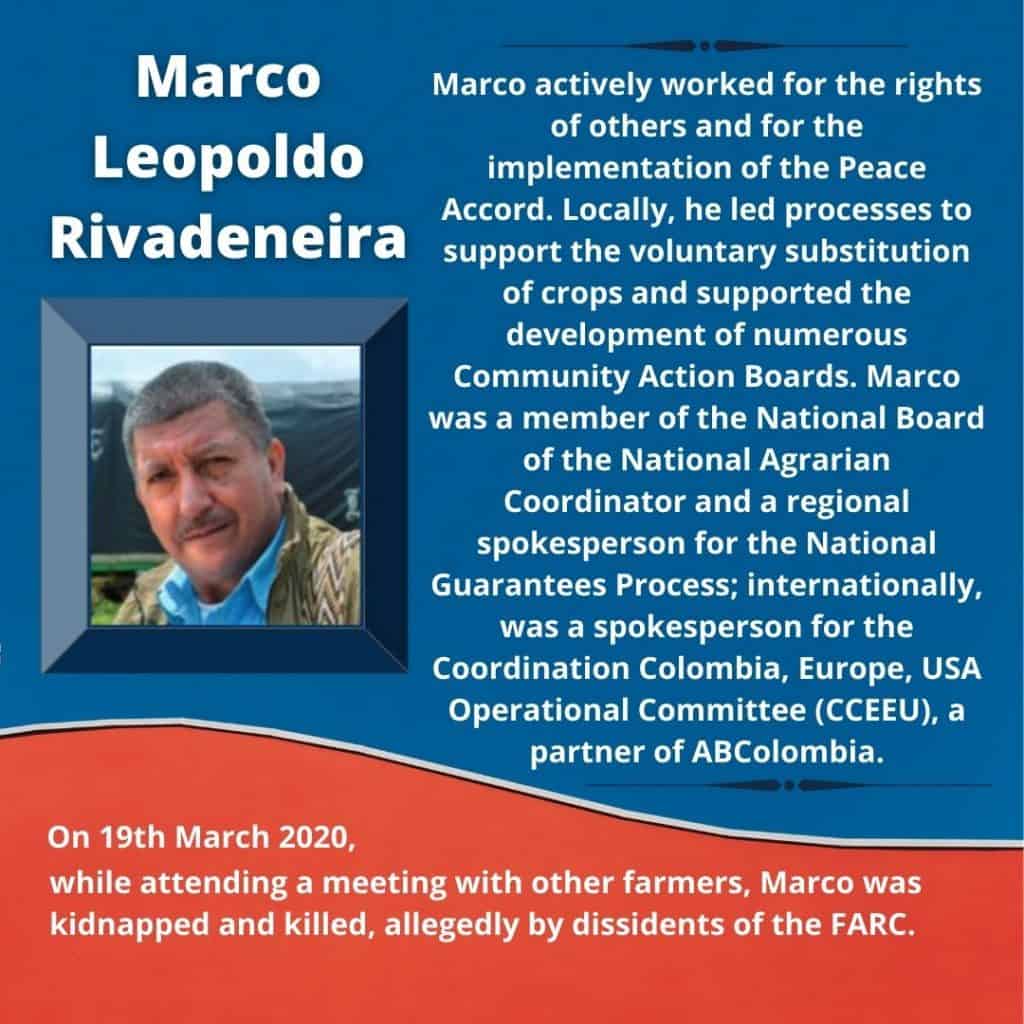

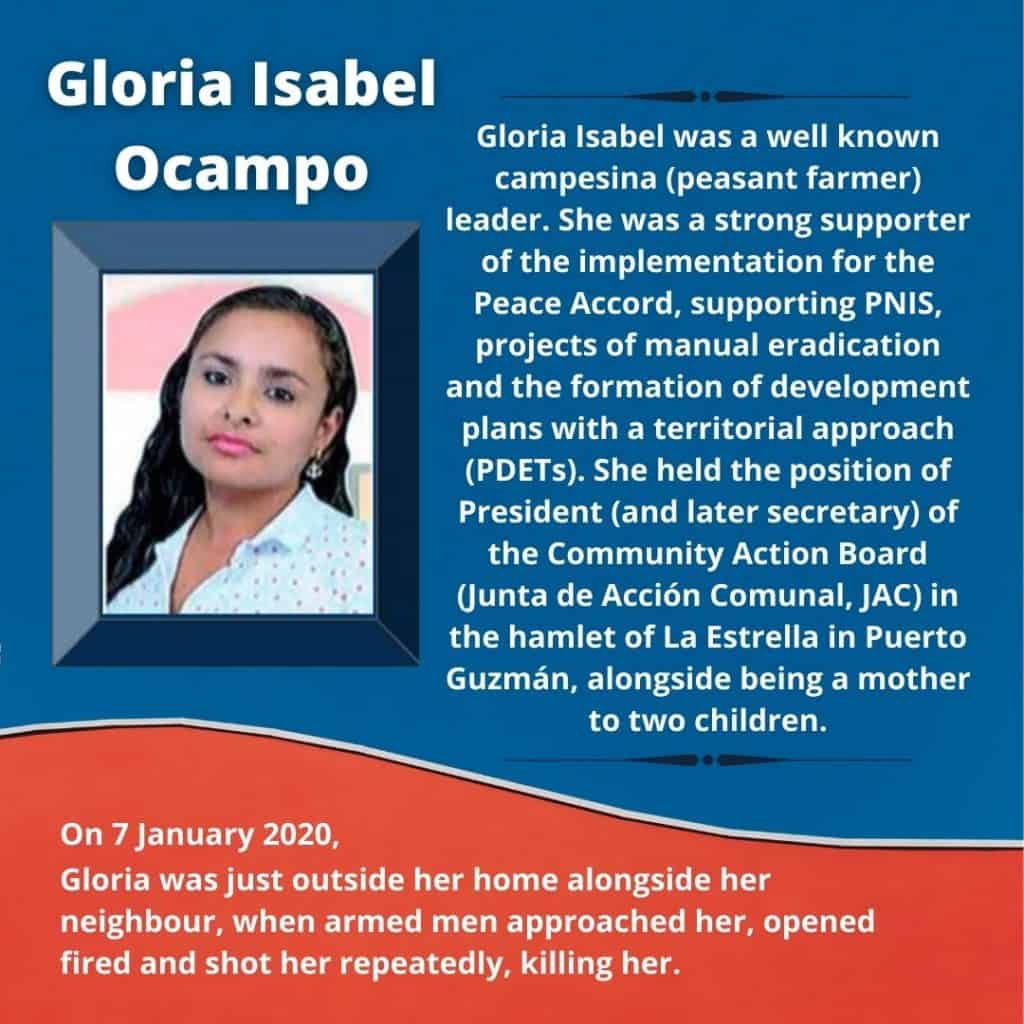

There has been a recent reconfiguration in the conflict which has led to further violence in rural areas particularly for those living in areas that are geographically strategic and/or rich in natural resources. Between 2018 and August 2020, FARC dissidents increased their operations from 56 municipalities, to 113; ELN from 99 to over 160, and neo-paramilitary groups to over 200 municipalities (Ávila, 2020). The Ombudsman’s Office denounced the presence of organised crime structures of regional, national and transnational scope, including the Mexican cartels, Sinaloa and Jalisco Nueva Generación, which are present in departments such as Córdoba, Chocó, Putumayo and Bajo Cauca and have a direct impact in the drug trafficking economy and significant capacity to harm the civilian population. [iii]

According to the Ministry of Defence, compared to the last year of the peace negotiations (October 2015 to September 2016) the number of victims of massacres in Colombia quadrupled in 2020 (October 2019-Sept 2020) and combats increased in the same timeframe by 65%. Homicide rates increased in the PDET areas by 36% in 2020, meanwhile outside of the PDET areas homicides rate decreased by 12%. Despite the increase in combats ELN deaths by the Security Forces decreased, deaths in the Security Forces are at their lowest point in the last twenty years, only deaths in neo-paramilitary and organised crime groups increased. According to Indepaz, the ideology of these groups is weakening and those perpetrating the attacks against communities and HRDs are less identifiable, as a result leaders and communities have less capacity to de-escalate the violence.

These statistic demonstrate that it is the rural civilian population that suffer the most from violence and social control.

Civil Society Organisations (CS0s) have been calling for the government to fully implement of PDET and the Voluntary Substitution of Illicit Crops Progamme (PNIS), together with other aspects of the Integral Rural Reform (RRI, Spanish acronym) chapter of the Accord. Slow progress in the implementation of these chapters, is exacerbating the violence.

Notes

Ávila, Ariel (2020) ¿Por qué los matan? Fundación Paz y Reconciliación