Emblematic Case: The Wounaan Indigenous People

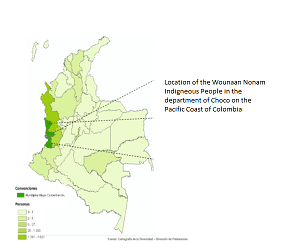

The Wounaan People are one of the Indigenous peoples in Colombia that are at risk of extinction due to displacement and violence, according to the Colombian Constitutional Court.[1] They live on the River San Juan near a dense rainforest in a particularly bio-diverse region in the South of Chocó. The Wounaan have been forcibly displaced on several occasions. El Espectador reports that 461 Embera and Wounaan were forcibly displaced between 2016 and 2017 alone, due to fights between the ELN, the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) and other paramilitary successor groups over territories that had previously been controlled by the FARC.[2]

In June 2011, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights awarded precautionary protection measures to 21 Wounaan families and ordered the Colombian State to “adopt the necessary measures to guarantee [their] life and physical integrity and […] their return to the Santa Rosa de Guayacán Indigenous Reservation in conditions of dignity and security.”[3]

However, the presence of illegal armed groups, military operations and the community’s location in a strategic corridor for drug trafficking exacerbated the security situation for the Wounaan. The community was too afraid to carry on their daily routine of tending to their crops, hunting in the forests and fishing in the rivers as the violent threats grew and they were constantly confronted by masked armed fighters. Fear for their lives and that of their children finally forced the Wounaan communities to flee to the port of Buenaventura in 2014.[4]

In Buenaventura, the Wounaan were relocated in a makeshift converted warehouse, where families slept on the floor for eleven months in one over-crowded living space. The conditions in which they lived lacked dignity with no water, no electricity and inadequate food. The new environment also did not allow them to continue with their traditional way of living.

In 2015, the Wounaan were able to return to their lands with the support of Christian Aid and CIJP, although they had little to no support from local institutions and their village was in a state of disrepair. As a result, they asked CIJP to help them establish Humanitarian and Biodiversity Zones. Communities see these Zones as offering security and protection.[5]

Humanitarian Zones: a concept that is used in Colombia by rural communities, whereby they cordon-off an area, often in a smaller portion of their territory. As a temporary measure, the community lives in this area. They obtain special protection measures from the Inter-American System for Human Rights and post signs around the cordon stating that this area is for the civilian population only and no armed actors are permitted to enter – legal or illegal. Find out more in ABColombia’s report on Self-Protection Mechanisms.

However, for some parts of the community, returning has been impossible, or solely temporary, given the continuing security threats posed by neo-paramilitaries.[6] After only 8 days of returning, the community of Unión Agua Clara, which had been declared as a Humanitarian and Biodiversity Zone, was forced back into displacement due to the lack of protections and the failure of the government to provide the minimum requirements for a dignified return.[7] Security in the area remains precarious to date.

In 2016, the Ombudsman noted that the situation in the Wounaan territories of Chachajo, Agua Clara and Chamapuro was so precarious that it was impossible to live in dignified conditions.[8] The presence of armed actors posed a continued risk to communities, and at least 200 families did not have access to clean water or electricity and there were no boats that could allow them to travel in case of an emergency.

In 2017, paramilitary forces abducted and tortured Wounaan community member José Cley Chamapuro.[9] More threats and intimidation from groups like the Urabeños and the planting of anti-personnel mines by the ELN in land near the indigenous territories were also reported.[10] The Wounaan Authorities’ Community Council (WOUNDEKO) also reported the forced recruitment of Indigenous children.[11] As a consequence of the violence in their surroundings, 900 Wounaan Indigenous people found themselves in situation of forced confinement in 2017,[12] and 141 Wounaan were once again forced to take refuge in Buenaventura.[13]

Lack of fulfilment of the commitments made by the government

The lack of measures by the National Government to ensure implementation of the Peace Accord in Buenaventura, particularly in relation to security and tackling/dismantling of paramilitaries as stated in point 3.4.3, increases the humanitarian crisis and vulnerability of the rights of communities living on lands that attract clear economic interests.[17]

Mauricio Redondo Valencia, Ombudsman Delegate for the Rights of Internally Displaced People, stated that despite the commitments made by local, departmental, and national authorities, the indigenous communities do not have the necessary guarantees to live on their ancestral lands.[18]

Since their displacement from their territory in 2014, six Wounaan children have died due to malnutrition and illnesses that could have been prevented had the government fulfilled its commitments to the indigenous communities.[19]

The Government has also failed to ensure a dignified return of the communities. Under the Land Restitution Law, the local government of Buenaventura has a duty to provide seeds, food, materials and transport for displaced communities to be able to return to their land.[20] However, not enough seeds were provided, the promised fishing nets are non-existent, there is no emergency transport and there are no mechanisms in place to collect rain water, forcing the communities to drink water from the river.[21]

Notably, the Victims Unit, which is responsible for ensuring the protection of the victims of the armed conflict under the Victims Law, provided families with a food basket, which was not appropriate for big Wounaan families and the food supplies that were provided for the first month were finished after only one week.[22]

The National Protection Unit has offered relocation of community leaders as a protection measure for the communities. However, the communities have criticised that this is inappropriate, because it would break the unity of the indigenous community. Most leaders want to stay in their territory and protect their communities and traditions.[23]

The situation today

Displacement and violence continue to affect Wounaan communities to date. In February 2018, in an operation against the ELN, Titan Security Forces bombarded an area close to the Wounaan indigenous resguardo of Chagpien Tordó, in the municipality of Litoral de San Juan in Chocó, injuring a 16-year old Wounaan girl and displacing the community.[24]

In July 2018, the church and civil society organisations in Chocó issued a public statement on the exacerbating humanitarian crisis in the department. The installation of landmines by the ELN again has led to forced confinement for local communities, including the Wounaan. This is affecting the security and survival of the Wounaan indigenous population in their territories, as it prevents them from cultivating and harvesting food crops on their territories or doing traditional crafts.

End Notes

[1] Corte Constitucional de Colombia, Auto 004/09.

[2] Indigenas en riesgo de extincion cultural en Colombia hablan en la CIDH (El Espectador, 10 May 2018)

[3] https://pbicolombia.org/accompanied-organisations/cijp/

[4] Towards a dignified return? (PBI Colombia, 18 December 2015)

[5] Towards a dignified return? (PBI Colombia, 18 December 2015)

[6] Towards a dignified return? (PBI Colombia, 18 December 2015)

[7] Desplazamiento de comunidad Woaunaan unión agua clara (Justicia y Paz, 9 December 2015)

[8] 600 indígenas no tienen garantías para retornar a sus territorios (Defensoria del Pueblo, March 2016)

[9] Continúa intimidación neoparamilitar (Justicia y Paz, 6 February 2017)

[10] Urabeños ingresan a territorio Woaunaan (Justicia y Paz, 22 April 2017) and Urgent Action: Wounaan Indigenous Community in Danger (Amnesty International, 20 July 2017)

[11] Urgent Action: Wounaan Indigenous Community in Danger (Amnesty International, 20 July 2017)

[12] Urgent Action: Wounaan Indigenous Community in Danger (Amnesty International, 20 July 2017)

[13] Desplazada totalidad de habitantes de Resguardo Santa Rosa de Guayacán (Justicia y Paz, 13 February 2017)

[14] Naciones Unidas alerta por el desplazamiento de 1.878 personas en el Pacífico (Semana, 29 September 2017)

[15] Desplazamiento de comunidad Woaunaan unión agua clara (Justicia y Paz, 9 December 2015)

[16] Muere 6ta bebé Woaunaan por falta de acceso a centro médico (Justicia y Paz, 29 March 2017)

[17] Desplazamiento forzado por enfrentamientos de estructuras neoparamilitares (Justicia y Paz, 3 November 2017)

[18] Defensoría verificó malas condiciones de indígenas que desde Buenaventura habían retornado a sus territorios (Defensoria del Pueblo, 23 March 2016)

[19] Muere 6ta bebé Woaunaan por falta de acceso a centro médico (Justicia y Paz, 29 March 2017)

[20] Los Wounaan de Unión Agua Clara piden que el Estado cumpla (For Peace Presence, 6 January 2018)

[21] Desplazamiento de comunidad Woaunaan unión agua clara (Justicia y Paz, 9 December 2015)

[22] Los Wounaan de Unión Agua Clara piden que el Estado cumpla (For Peace Presence, 6 January 2018)

[23] Los Wounaan de Unión Agua Clara piden que el Estado cumpla (For Peace Presence, 6 January 2018)

[24] Colombia: Bombardeo cerca de un territorio indígena en el Chocó (Amnesty International, 1 February 2018)

[25] La crisis humanitaria del Chocó según Human Rights Watch (Contagio Radio, 7 June 2017)