Voices from the River Atrato Chocó

Chocó department in Colombia is located in the Pacific basin of the “Chocó Biographical Region.” It extends from the Andes mountains to the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. It is one of the most important tropical regions in the world, being a nucleus with a high concentration of biodiversity and endemic species. It has nine types of biomes and 55 differentiated ecosystems. Its high rates of vegetation cover, forests, mangroves and jungles make it a key carbon storage epicenter to combat the effects of climate change. It is also crucial to the migration patterns of hundreds of species, including humpback whales off its Pacific coastline. Chocó reports one of the highest rates of rainfall, averaging 9000 mm of rain p.a, and freshwater circulation on the planet. Its territory has over 50 sub-basins that drain towards the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean, the most important is the Atrato River, its waters flow into the Caribbean Sea it forms a complex deltaic system, known for being the nesting and birthplace of sea turtles.

Choco has some of the world’s wettest rain forests. In the Choco-Darien ecoregion there are at least 8,000 vascular plant species of which almost 20% are found nowhere else in the world. This rich plant life that provides the Indigenous and Afro-Colombian Peoples with natural medicines important for the health and cultural practices of the indigenous and Afro-Colombian peoples. Many of their medicinal plants are endangered due to environmental destruction generated by deforestation, illegal mining, cultivation and processing of coca.

It is an area rich in natural resources that suffers from the conflict. A Peace Accord with the guerrilla groups – FARC-EP – was signed in 2016. However this was the largest of the guerrilla groups, the second largest group continues in the conflict to day – the Ejercito Nacional de Liberacion (ELN) as well as neo-paramlitary groups like the Auto-defensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) and other criminal groups. The ELN and AGC and some dissidents of the FARC continue to engage in skirmishes for control of people, territory and illicit economies in Choco. As a result of ongoing conflict and state neglect the Pacific Coast of Colombia is suffering a humanitarian crisis.

Yet it is an area where community leaders are active and resilient in the defence of the rights of their communities. In an effort to peacefully defend their territory they established links with a range of national and international NGOs who support them in their struggle to defend their rights, their land and the biodiversity of Choco, national NGOs like Tierra Digna, the Social Justice Centre -Siembra, and the Catholic Dioceses of Quibdo, Istmina and Apartado (in Choco) and international organizations SCIAF, CAFOD and ABColombia. As well as academic institutions in the UK like Glasgow, Portsmouth and Nottingham Universities.

They achieved a landmark ruling from the Constitutional Court giving bio cultural rights to the Atrato River (the most important river in Choco). This ruling, along with a similar one from a court in New Zealand, set a global precedence on the rights of rivers. The Colombian Court acknowledged the inherent interdependence between the environment and communities in the Atrato region and ordered the Government to take a series of measures to protect the Atrato River and combat illegal mining and deforestation in the region reiterating the right to free, prior and informed consent for ethnic communities.

In May 2021, G7 Climate and Environment Ministers expressed their “grave concern that the unprecedented and interdependent crises of climate change and biodiversity loss pose an existential threat to nature, people, prosperity and security.”

Choco is also a region of ancestral importance, occupied by five different indigenous tribes living in resguardos (reserves), alongside Afro-Colombian communities (this region received Afro-Colombians after liberation when they overcame slavery). The Constitution of 1991 created the possibility for Afro-Colombians living in Choco to apply for special collective land titles governed by elected councils. The population of Choco is unlike any other department in Colombia with over 92% of its population being Afro-Colombian or Indigenous living on collectively owned territory. Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities depend on the river Atrato and its tributaries for their livelihoods, means of subsistence and cultural practices.

It is impacted by climate change, and experiences disasters such as flooding. It has little access to drinking water and waste removal and is prone to vector borne diseases including Dengue fever and malaria. It is one of the poorest regions of the country it lacks the resources to manage climate change impacts. It has been historically neglected by the Colombian state suffering from lack of basic services.

Conflict has ravaged Choco and its communities since the 1990s as armed groups sought to control communities, territory and illicit economies (such as gold mining, coca growing and deforestation). Paramilitary groups that demobilise admitted to an orchestrated plan in the Choco-Urabá region of forced displacement and land grabs. This land was then handed over to ago-industrial projects like oil-palm. Paramilitaries and security forces at times acted together and at others in collusion to displace communities in on the Pacific Coast of Colombia in operations like that of Operacion Genesis. Often using brutal violence which caused communities to flee in terror. FARC -EP and the ELN guerrilla groups often confined communities in their territory. All armed actors used indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities as human shields in their struggle for territorial control. Community and Church leaders were threatened and killed.

“My community was displaced in 1997 by violence I was 17. We all had to leave, driven out by paramilitaries and the army. There was also bombing. They attacked because our territory is rich in natural resources. There were economic interests in the land by large scale farming businesses who wanted to produce palm oil and bananas… So, we went to the neighbouring department of Antioquia. We had to walk for two weeks through the jungle, with pregnant women giving birth. The oldest people died. We were about 6000 people. Eventually we had to stop, we were so tired. We made makeshift houses out of branches and plastic sheets.

After a year we returned to our territory. But things were different. We built hamlets, close together for protection and so that we could watch out for each other. Some returning communities found that all their land had been planted with palm oil and their homes had been totally destroyed…”

“The water ran very clean and pure, very different from now. It’s no longer clear and has lots of sediment and is not so deep. It began to change when the mining started, from the 1990s onwards.

“When I was young, by 2 or 3 years old we knew how to swim and were always in the river doing lots of things there: swimming, playing in little canoes, and fishing. There was an immense variety of fish in the river. There were lots of trees, and we saw animals all the time – deer, jaguars, sheep, leopards, armadillos… Now that there is deforestation and mining

My children cannot have same relationship with the river now. There are chemicals in the water, and we don’t want to jump in anymore. …In the summer it used to be very clear, we could see to the bottom of the river and drink it. Now drinking the water gives people diarrhoea so we must use filters or boil it. Some people use rainwater…” The river is a source of life for communities living along its banks. However, as a result of illegal mining activities and the continued armed conflict, the river has suffered greatly.” “The rivers are a vital part of my people. If the river dies – if it becomes polluted beyond repair – then I die with it.

Today, Community leaders are being killed in incredible numbers as they seek to protect community, land and environmental rights. In 2020 alone, 120 human rights defenders were killed in Colombia. The majority from Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities. Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world to be a human rights defender.

Environmental Destruction and Climate change

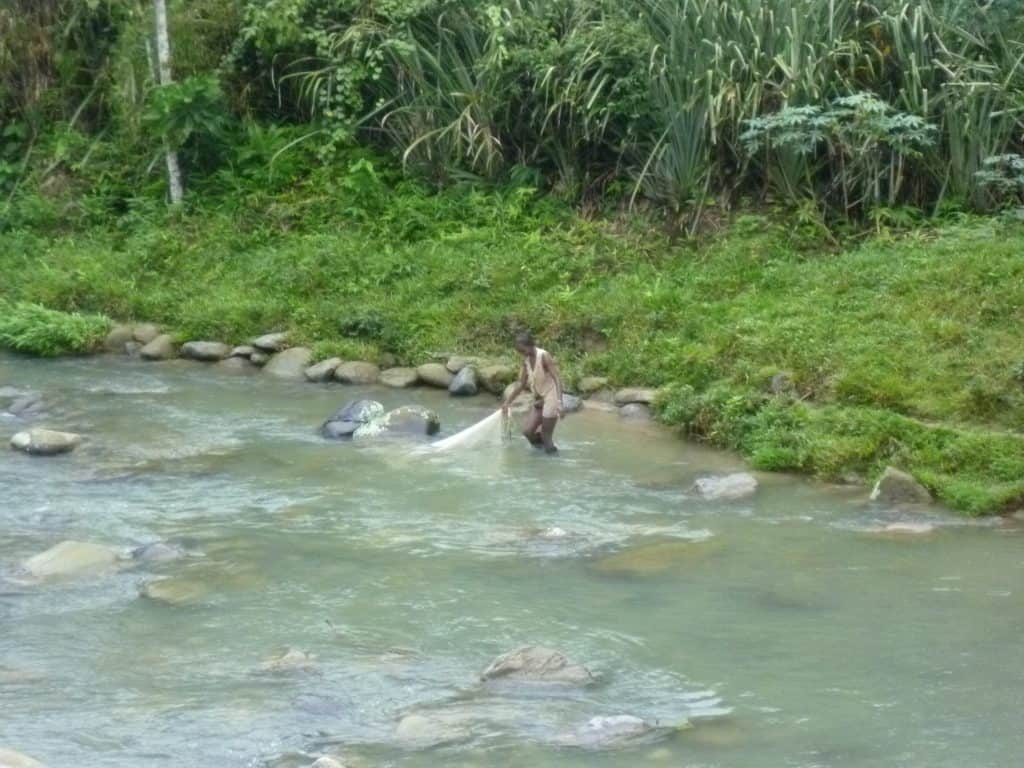

Whilst the conflict and land grabs are prevalent along the whole of the Atrato, the environmental disasters it suffers vary, from illegal gold mining protected by illegal armed groups, to deforestation and the impacts of coca growing, along with changing climate patterns causing increased flooding. In many of the tributaries of the Atrato river, gold mining protected by illegal armed actors, is causing conflict, an environmental and humanitarian disaster– the Rio Quito pictured above.

Defence of the river Atrato

The Department of Choco, in spite of the harsh conditions such as, the armed conflict, exclusion and racial discrimination, is characterised by its people who have been persistent in organising themselves, in demanding structural changes, creating human rights networks, vindicating their way of life and their culture

For years, alerts by the Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities concerning the urgency of the problems in the Atrato region were met with indifference by the Colombian government. These problems culminated in an unprecedented environmental and humanitarian crisis due to the contamination of the river with toxic substances, erosion, accumulation of waste, deforestation and loss of biodiversity. This crisis has been further exacerbated by the realities of the armed conflict.

Forestry waste products have filled the river basins. The lack of sewage systems and landfills in the municipalities near the river contributes to ongoing waste disposal into the river. Chocó has historically hosted communities that exploit precious metals through artisanal mining methods.

However, from the 1990s onwards, extraction methods began to gradually change. Intensive machinery use (mainly suction dredgers, hydraulic elevators and backhoe excavators) and toxic chemical elements, such as mercury and cyanide were introduced. Currently, the Atrato River basin hosts multiple illegal small and medium-scale mining exploitation projects. These are protected by illegal armed actors making it very dangerous for community leaders who are seeking to stop this environmental destruction. There are more environmental and land defenders killed in Colombia than anywhere else in the world

Global economics and the armed conflict have facilitated and supported the increase of illegal gold mining. The methods of extraction used by the miners, and the sediment and mercury that they have released, has altered the course of the river, increased water turbidity and released toxins into the environment. In turn, this has reduced fish stocks due to the density of the sediment, the remaining fish are absorbing mercury from the water which then enters the food chain and the agricultural land along the riverbanks is being destroyed, all of this has reduced communities’ access to sustainable sources of food.

Conflict, destruction of the river and reduction in food sources left the communities in a very difficult situation with few choices available to them. They could accept the expansion of illegal mining and destruction of their territory to access new sources of income and livelihoods or take action to address this situation. They decided to address this situation through recourse to the law, since all of their reports to State authorities had not only gone unheard but had resulted in death threats and killings of community leaders, and no action on the part of the State.

The communities working with Colombian NGO Tierra Digna undertook studies, collated data, and together submitted evidence to the Court that mechanised mining activities contributed to an exponential increase of problems in the region, causing massive and systematic violations of the fundamental rights of the communities. One example of this was were 37 children died after drinking poisoned water, and 64 children suffered the consequences of poisoning. Diseases like diarrhea, dengue and malaria had all also increased.

Landmark Court Decision

In the absence of an adequate Government response to the dire humanitarian situation and the destruction of the community’s territory and the environment, Tierra Digna/Siembra sought a legal decision. The Government denied responsibility for the human rights violations. The Court found that state authorities were indeed responsible for violations of the right to life, health, water, food security, the right to a healthy environment, as well as the cultural and territorial rights of the claimant ethnic communities. The authorities had failed to comply with their constitutional obligations. The landmark judgement T-622 gave biocultural rights to the Atrato River and its tributaries. Based on an extensive analysis of international law, the Court introduced the concept of biocultural rights into Colombian Constitutional Law. Granting these rights to the river recognised the interdependency between nature, natural resources and the ethnic communities. The Court emphasised that an ecocentric approach to human rights acknowledges that preserving biodiversity is intrinsically linked with the preservation and protection of different forms of human life and cultures.

In summary, biocultural rights are the precondition for the rights of ethnic and Indigenous communities to exercise territorial autonomy in accordance with their own laws and customs. This includes the right of communities to administer the natural resources in the territories in which they have developed their culture, traditions and their special relationship with the environment and biodiversity. In an unprecedented interpretation of constitutional law, the Court went as far as pronouncing the Atrato River itself as legal subject with specific rights regarding its protection, conservation, maintenance, and rehabilitation.

A clean and healthy environment is a very basis of human life, as are balanced ecosystems, biodiversity, and other elements of nature on which people depend, which is why this Court decision is so important, not only for the communities, but also for biodiversity and in order to address climate change. The Court also reiterated once again the right to free, prior and informed consent for ethnic communities.

The Court ordered that a group of 14 elected community member from communities along the Atrato River and the Colombian Environment Minister be named as Guardians of the Atrato, responsible for ensuring the implementation of the ruling T-622.

The mechanisms for participation, monitoring and scientific reports built into the T622 ruling produced a Comprehensive Climate Change Plan (CCCP) consulted with communities. However, this process is very bureaucratic initially excluding the communities who have had to struggle to get their voice heard.

The implementation is slow to non-existent at the moment, and it will be necessary to strengthen cooperation in adaptation and resilience programs that directly benefit local communities and to ensure effective implementation of the CCCP, based on independent scientific expertise.

The communities formed a group of national and international advisers made up of NGOs, academic institutions, and lawyers. This national and international approach has brought about interesting results in biodiversity restoration and in building resilience.

As well as, providing tools through citizen science projects and radar satellite monitoring to enable communities to track deforestation linked to mining and damage to the river’s ecosystems, creating the scientific data, backed by a Court decision, to base their insistence that the relevant state authorities take action to address this situation.

During the pandemic this information collated via satellite mapping was able to be sent to the Comite de Seguimiento (Monitoring Committee) set up by the Court, in order for them to question the Ministry of Defence on what actions they were taking to prevent and to dismantle the mining operations on the Rio Quito. You can see from the slide the rapid increase in mining activities during the pandemic, this also increased violence against communities and control of their movements by armed actors protecting the mining operations.

Guardian of the Atrato River in conversation with ABColombia: “What we have achieved has been to convince the Colombian government that the environmental action plans must be designed by the communities with a territorial development approach and a bio cultural approach, and in that aspect we are slowly making progress…The difficulties we have are in getting the government to understand that the Atrato area environmental action plan must have a differential approach in all of its aspects (ethnicity, gender, culture and territorial)…And although we have made progress now in the planning, the greatest difficulty is to get the implementation started ..to date the government has not designed the methodology for implementation on the ground…”

“The greatest threats we suffer is that the Court order related to the dismantling of illegal mining in the territory has not been implemented.”

Implementation, monitoring and evaluation programmes should be co-designed with the communities’ representatives the Atrato Guardians. This is not just in the spirit of the bio-cultural rights enshrined in the Court Ruling but also recognising the historic knowledge of riverine citizens. Monitoring and Evaluations systems will require significant investment to ensure that information is collected to support meaningful evaluation. Much work and many challenges still confront the communities, but these initial first steps set precedence, for replication in other regions of the world.

Respecting and protecting human rights and protecting the environment are inextricably linked. Chocó is key for global climate change mitigation – as a major carbon sink – but if it continues to be destroyed it will no longer provide this important ecosystem service. The communities are at the forefront of protecting the Chocó ecosystem and are key stakeholders in addressing climate change in this region.

Respect for, protection, promotion and fulfilment of human rights, and the protection of those who defend them, must be an essential and non-negotiable part of measures adopted in upcoming negotiations at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, COP26.

Visit our stand in the Green zone and our Website for more information