2020 is proving to be one of the worst year’s on record for the killings of Human Rights Defenders (HRDs)...

Category: News

Death of Javier Ordóñez Leads to Calls for Police Reform

According to official figures ten protesters have been killed and over 200 civilians injured, allegedly, due to an excessive use...

How Mining Companies Silence and Nullify Actions by Indigenous Peoples to Protect their Rights

Tickets for this Webinar free here Indigenous Peoples in Colombia struggle to protect their human, cultural and environmental rights. They...

Amicus Brief: Arroyo Bruno

ABColombia and the Colombian Caravana UK Lawyers Group in August 2020 filed an Amicus Brief before the Court of Execution...

Ex-President Uribe under House Arrest

The Supreme Court of Colombia has placed former President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) under House Arrest.. Uribe Vélez is currently a...

Lack Colombian Government Commitment to Security for Former Combatants?

Colombian Interior Minister Alicia Arango Olmos failed to attend the CSIVI meeting called to address the deteriorating security situation for...

Illegal Surveillance of Colombian Human Rights Defenders

Letter to Colombian Government from International NGOs and Legal Organisations on alleged illegal surveillance by the Colombian Military ABColombia joined...

Transitional Justice System in Colombia under Attack

International Civil Society Organisations reject the repeated attacks and accusations against the Truth Commission Civil Society Organisations reject the repeated...

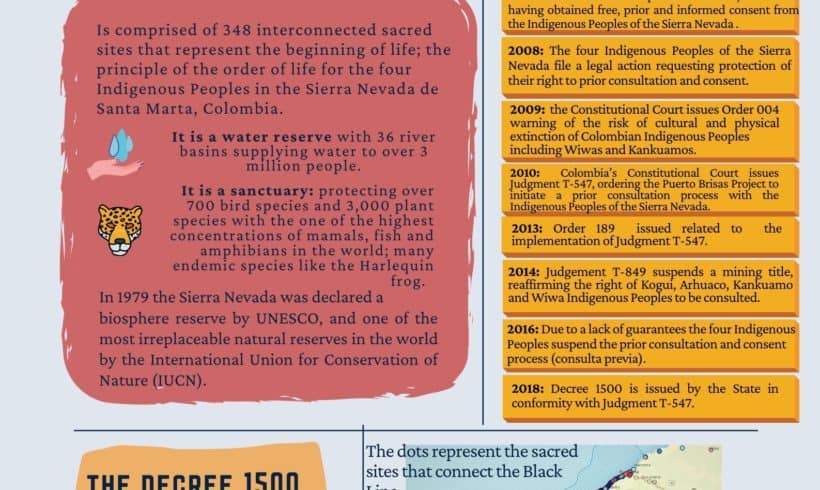

Linea Negra Decreto 1500

After years of consultation by the four Indigenous Peoples of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta: Kogui, Arhuaco, Kankuamo and...

What are the Lungs of the Earth without the Heart?

PRESS RELEASE UK Lawyers Submit Amicus Briefs in Support of Indigenous Peoples in Colombia Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta: Heart...